|

| Home ⇒ golf ⇒ biomech ⇒ Current Article |

Article

Contents

Application to the golf swing

|

Function

These are rather broad performance goals, and they depend on impact conditions

-- that is, the position and motion of the clubhead with respect to the

ball at the moment of impact. That means we need to state the

performance goals in terms of the desired impact

conditions that we want out of the swing. |

| Biomechanics |

Impact conditions |

Performance goals |

|

|

|

Golf biomechanics is the making the items in the "Biomechanics" column cause the performance goals to be met. But the performance goals depend on the impact conditions. Only the impact conditions. That is perhaps an overstatement, but not as far as biomechanics are concerned. The other conditions are things like wind and the condition of the ground where the ball lands. They have nothing whatsoever to do with biomechanics.

As my friend John Ford is very fond of saying, "The ball don't know!" The ball only knows the the clubhead is doing at the moment it impacts the ball.

It doesn't know whether the golfer was in balance during the

swing.

It doesn't know whether the golfer had a still lower body or active legs and hips.

It doesn't know the position of the wrists or lead elbow.

It doesn't know whether the ratio of backswing to downswing time was a perfect 3.0.

It doesn't know whether the alpha torque is positive or negative.

The ball only knows what the clubhead is doing during the

4/10,000 of a second the ball and clubhead are in contact.It doesn't know whether the golfer had a still lower body or active legs and hips.

It doesn't know the position of the wrists or lead elbow.

It doesn't know whether the ratio of backswing to downswing time was a perfect 3.0.

It doesn't know whether the alpha torque is positive or negative.

That means that the only thing biomechanics can do to make a difference in performance is to control the impact conditions so they achieve the performance goals. Let's break down how that works:

- Biomechanics'

job is to make the clubhead's motion be what we want during the instant

of impact -- to create the desired impact conditions per the table.

- Converting those impact conditions into launch conditions

is not biomechanics; it is the job of the impact model.

We will say something about this below.

- Converting those launch conditions into distance, direction, landing, etc is not biomechanics either; it is the job of a trajectory model -- a mathematical model reflecting how gravity, aerodynamic drag, and aerodynamic lift operate on the golf ball. The trajectory model is discussed elsewhere. so we will only mention a few important points about it here:

- More ball speed almost always means more distance. It takes a really strange launch to give a different result.

- You hear about wanting high launch and low spin for more distance. What you don't usually hear is that you need both. A few truths to bring that point home:

- If you increase launch without decreasing spin, you may actually lose distance to ballooning.

- If you decrease spin without increasing launch, you may actually lose distance because the ball doesn't have enough lift to keep it in the air.

- Here's a corollary to these points. I have heard, more

than once, a TV announcer saying something like, "He had 2700rpm on

that drive. That's way too much spin; he is losing distance." The

complete launch monitor readings on the TV screen showed a very low

launch. The real problem was

the low launch, not the high spin. In fact, with that low a launch, he

needed the extra spin to get any reasonable distance at all.

Function: The impact model

The impact model is a mathematical description of what happens at impact to convert the impact conditions into launch conditions.The impact model starts with the four items identified in the table above in the column "impact conditions".:

- Clubhead speed.

- The D-plane.

- Position of impact on the clubface.

- Bottom of swing. (I added that

to the usual impact model, because it does affect the other impact parameters.)

- Ball speed.

- Ball direction, both vertical (called "launch angle") and horizontal.

- Spin, both vertical and horizontal. It can be specified as

either [backspin, sidespin] or [total spin, angle of tilt]. Either one

might be appropriate, depending on what problem you are trying to solve.

Clubhead speed

The most easily quantifiable goal is clubhead speed. It is also one of the easiest to "sell", because clubhead speed turns directly into distance and, as everybody in the golf business knows, distance sells! It is easy to quantify how clubhead speed turns into distance. For a well-fitted driver struck on the sweet spot, every extra mile-per-hour of clubhead speed turns into 3 extra yards of carry distance. (I did a study on that some years ago, if you want to see how I know that -- and what it actually means. BTW, many people read the wording of that statement to be different from what it actually says; if you want to know what it means, read my article.)For these reasons -- easily quantified, and high value because it means distance -- clubhead speed is probably the most frequent candidate for optimization in golf biomechanics. But it is hardly the only one. Let's look at other aspects of the impact model.

The D-plane

The D-plane was first described (to my knowledge, anyway) by Theodore

Jorgensen in his book "The

Physics of Golf"

(1994). It is important because it is the major contributor to spin,

trajectory height, and curvature of the ball's flight. The plane itself

is identified by a well-known piece of geometry: two intersecting

straight lines define a plane. The D-plane is the plane defined by two

vectors:- The 3-dimensional direction the clubface is pointing.

- The 3-dimensional path of the CG of the clubhead.

| Plain

English |

Component |

Golf

jargon |

| Direction

the clubface is pointing |

Vertical |

Dynamic

loft |

| Horizontal |

Face

angle |

|

| Path

of the clubhead's CG |

Vertical |

Angle

of attack (AoA) |

| Horizontal |

Clubhead

path |

For a better visual understanding, let's look at a picture.

- The initial direction of the ball leaving the club is another vector that lies in the D-plane.

- The spin of the ball is oriented so that it is in the D-plane; its axis of spin is perpendicular to the D-plane.

- The amount of spin is proportional to the "obliqueness". Obliqueness is the angular difference between the face direction and the path of the clubhead's CG. If the face and the path are in the same direction (zero obliqueness), then there is no spin.

- By the same token, having the face and path lined up the

same gives a very solid hit, and maximum ball speed. Ball speed falls

off with increased obliqueness. But not proportionally. Ball speed fits

well to the cosine of obliqueness, not much all at first but greater by

increasing amounts as the angle grows. For example, only 1% of ball

speed is lost at an obliqueness of 8°. But the loss is 4% at 16°, and

9% at 24°.

The

initial direction of ball flight is in the D-plane. It is pretty close

to the face direction. How close? For a driver, the percentage is about

85% face and 15% path. What that means is that angle B (ball

direction) is 85% of angle Q (obliqueness).

As the total obliqueness Q

goes up, the

percentage goes down. But it never drops much below 70%, even for

wedges. But, at least for drives through middle irons, it is a pretty

good approximation to say the ball starts out in the direction the face

points.

The

initial direction of ball flight is in the D-plane. It is pretty close

to the face direction. How close? For a driver, the percentage is about

85% face and 15% path. What that means is that angle B (ball

direction) is 85% of angle Q (obliqueness).

As the total obliqueness Q

goes up, the

percentage goes down. But it never drops much below 70%, even for

wedges. But, at least for drives through middle irons, it is a pretty

good approximation to say the ball starts out in the direction the face

points.

- The aerodynamic lift on the ball is in the D-plane; that is

because the spin is completely in the D-plane. The lift force is

perpendicular to the flight of the ball; it isn't straight up as you

might guess from the name. If the D-plane is tilted the lift has a

horizontal component, which manifests itself as hook or slice.

- The lift is proportional to the spin, which in turn is proportional to the obliqueness angle Q.

- Distance is generally hurt by increased obliqueness. (Exception: for obliqueness under about 15°, Q is one of the parameters that can be "tuned" to optimize distance for a given clubhead speed.) Several reasons for this:

- Increasing obliqueness decreases ball speed.

- For larger Q (say, more than about 15°), the obliqueness comes mostly from loft, and increased loft decreases distance.

- Increasing obliqueness increases spin, which increases

lift. Note that lift is not vertical, it is perpendicular to the ball

flight. That means lift has a backward component (look at the diagram)

while the ball is rising, which generall limits distance a lot more

than the helping component when the ball is descending. When you hear

the term "ballooning", this is

what is causing the problem.

Position of impact on clubface

Everything we have covered so far on the impact model assumes a center-face strike. Before we talk about off-center strikes, let's review what an on-center strike means. It has little to do with the markings on the clubface -- though club designers do and should place the markings so they correspond to a center strike. But it really has to do with forces and moments.When the clubface strikes the ball it exerts a force on the ball. A very big force! What impact does is accelerate a golf ball from a standstill to, say, what a driver would do to it with a clubhead speed of 100mph. And it has to do it in 0.0004 seconds. We know the mass of the golf ball: 46g, and 100mph=44.7m/s. We are analzying a center strike, so we'll use the ideal smash factor of 1.48. So it is just math and physics to determine that:

ballspeed

v = 44.7m/s * 1.48 = 66.2m/s

a = v/t = 66.2m/s / 0.0004sec = 165,500 m/s2

F = ma = 0.046kg * 165,500m/s2 = 7613N

a = v/t = 66.2m/s / 0.0004sec = 165,500 m/s2

F = ma = 0.046kg * 165,500m/s2 = 7613N

...or, in American units, 1711 pounds. And that is the average over impact; the peak force can easily exceed 2500 pounds.

Side note, but important: If any of this calculation was confusing, then you need to go back and review Book 1 -- Physical Principles. This is really basic physics. You'll need to know more than this to understand the biomechanics of the golf swing.

So the clubhead applies a force averaging about 7600N (1700 pounds) to the golf ball during impact. The force's direction is lined up with the ball's launch direction, because it is the force that caused the acceleration leading to launch. Newton's laws say that the ball must apply an equal and opposite force to the clubhead. That's the yellow force vector in the diagram.

Note that the force goes through the center of gravity of the clubhead. That is the physical definition of a center strike.

If you are able to achieve a strike like this, with the reaction force through the CG of the clubhead, the head will remain stable through impact and well into the follow-through. You won't see it twist open or closed after impact. If you do see it doing some interesting twisting post-impact, that should tell you the strike was off-center. So, let's see what happens in an off-center strike.

In

this diagram,

the ball strike is toward the toe of the clubface. The reaction force

(still shown in yellow) no longer passes through the CG. In fact, the

distance from the CG to the force is a moment arm, and moment arms imply a

torque and often an angular acceleration. Why should this be?

In

this diagram,

the ball strike is toward the toe of the clubface. The reaction force

(still shown in yellow) no longer passes through the CG. In fact, the

distance from the CG to the force is a moment arm, and moment arms imply a

torque and often an angular acceleration. Why should this be?In the section on Torque, we saw that an object, absent something holding it in place, will tend to rotate around its CG in response to a force not through the CG. Put more simply, the center of gravity of the object wants to stay where it is; it will tend to do so, act as a pivot, and let forces not through it exert a torque to rotate the object. How much angular acceleration it gets from the rotation depends on the moment of intertia of the object, and moment of force. That moment of force is the force times the moment arm, and the moment arm is defined as the perpendicular distance from the CG to the line of the force.

So the off-center force in the diagram will exert a torque on the clubhead, clockwise in direction, and of a magnitude equal to the force times the moment arm. "Clockwise direction" means the clubhead will rotate open as a result of the strike. Let's see what this impact statement says about launch conditions.

Here

we show the clubhead rotating in a opening direction, as the toe-side

force will make happen. It is rotating around the CG, as it should; the

CG is the spot on the clubhead that wants to remain in place. The red

arrow shows the motion of a single point on the clubhead. This is a

special point: the spot where the ball is in contact with the clubface.

Here

we show the clubhead rotating in a opening direction, as the toe-side

force will make happen. It is rotating around the CG, as it should; the

CG is the spot on the clubhead that wants to remain in place. The red

arrow shows the motion of a single point on the clubhead. This is a

special point: the spot where the ball is in contact with the clubface.What does this do to the golf ball, during the brief instant it is on the clubface? We have to remember that it is not just sitting on the clubface; it is being pressed hard against it by a force of nearly 2000 pounds. If there is any friction at all between the ball and the clubface, such a large normal force means there will be a large friction force as well. So the point on the ball that is touching the clubface will act as if it is stuck to the clubface. Let's see what that means for the launch parameters of the ball:

At the point of contact between ball and clubface, the red arrow showing motion has a speed and a direction, so it is a vector. Let's deal with its two components: (a) motion tangent to the clubface, and (b) motion perpendicular to the clubface.

- The tangent motion, through friction, causes the corresponding point on the ball to move in sync with the clubface, with zero or minimal slippage. That spins the ball in the opposite angular direction from the clubhead; see the blue arrow for ball spin. It is as if the clubhead and ball are pinion gears; if one rotates, the other has to rotate in the opposite direction. It is not surprising that this is called "gear effect", and I have an article that goes into it in great detail.

- The tangent motion has another effect as well. The gear effect from the previous bullet point comes from the moment of force that the tangent friction imposes on the golf ball. But it is also a force, not just a moment. That means it is accelerating the ball in the direction of a push.

- There is also a perpendicular component of the clubface motion, and it is away from the ball. There is an obvious implication; that component of the motion is detracting from the clubhead speed, so it will not impart as much speed to the ball. That is why an off-center strike has a lower smash factor than a "sweet spot" strike. The clubface is retreating from the ball, reducing the clubhead speed seen by the ball.

- Wouldn't the clubhead tend to rotate around the shaft? That is where it is attached to the rest of the world, so why wouldn't that be the pivot, not the CG?

- What happens if the CG is in the clubface (like a blade iron) rather than well behind the clubface (the driver in our examples so far)?

We'll get to #1 in a

second, but first let's talk about #2. This diagram shows a club with

negligible weight behind the face, so the CG is almost in the face.

When the clubhead rotates around the CG, the point of contact between

ball and clubhead still follows a curved path. But -- the key point

here -- that curved path is perpendicular to the face where it meets

the face. That means there is no component of the movement tangent to

the clubface during impact, and therefore no gear effect causing spin.

But there is still a perpendicular movement, so the clubface retreats

from the ball during impact and causes loss of ball speed. Even with a

blade iron, there is a distance penalty for missing the sweet spot.

(Actually, because of moment of inertia, the penalty is greater for a

blade than a cavity back. But that's a detail you'll have to look for elsewhere; it's way outside

the domain of a biomechanics discussion.)

We'll get to #1 in a

second, but first let's talk about #2. This diagram shows a club with

negligible weight behind the face, so the CG is almost in the face.

When the clubhead rotates around the CG, the point of contact between

ball and clubhead still follows a curved path. But -- the key point

here -- that curved path is perpendicular to the face where it meets

the face. That means there is no component of the movement tangent to

the clubface during impact, and therefore no gear effect causing spin.

But there is still a perpendicular movement, so the clubface retreats

from the ball during impact and causes loss of ball speed. Even with a

blade iron, there is a distance penalty for missing the sweet spot.

(Actually, because of moment of inertia, the penalty is greater for a

blade than a cavity back. But that's a detail you'll have to look for elsewhere; it's way outside

the domain of a biomechanics discussion.)The center of mass of an iron head can't be as far forward as the clubface itself. But it is much closer to the clubface than a driver, or even a fairway wood or hybrid. With "hybrid-irons" or irons with a big flange and a wide sole, the gear effect may not be negligible at all.

Let's get back to issue #1: why would the club rotate around the CG rather than it's attachment point at the hosel. It all comes down to forces and torques. Let's looks at the force of impact, and see which "pivot" is better able to absorb that force and stay in place.

- We know the force of impact for a 100mph swing is about 1700 pounds, averaged over the 0.4 milliseconds of impact.

- The clubhead mass of a driver is 200g. If you apply a 1700-pound force to a 200g mass for 0.4 msec, you will accelerate the mass so it moves about an eighth of an inch. Sounds like it is resisting the force pretty well.

- A stiff-flex shaft will deflect about a half inch for each pound of force applied to it. If you apply a 1700-pound force to that shaft, it will deflect 850 inches, which is about 70 feet. That is obviously ridiculous; if the shaft were providing the resistance to impact forrce, then the clubhead would have gone straight back 70 feet during impact!

It turns out the shaft does have a small effect, but it is small.

- The ball is launched in a direction more away from the CG.

- Spin is added in a direction to curve the ball toward the CG.

- The further from the CG that impact occurs, the more the

change in launch direction and spin.

Bottom of swing

The next point I want to talk about is where the bottom of the swing should be. "The bottom of the swing" means the lowest point of the clubhead during the arc of the downswing and follow-through. What I espouse here is agreed with by every golf instructor I have ever run across. Its importance -- its place in the priority list of criteria for a good swing -- may differ from instructor to instructor, but most of them rate it pretty high on the list. And several consider it the single most important thing for a golf swing to accomplish. Here are a couple of sources which share that opinion:- Adam Young's book "The Practice Manual" (2015).

- Bobby Clampett's book and video "The Impact Zone" (2007 for the book).

The clubhead moves along an arc as it approaches the ball. Where it is in that arc when it strikes the ball will determine the impact parameters we discussed earlier. But there is an additional consideration: where the lowest point of the arc is with respect to the ground. This is important for every shot where the ball is on the ground. (Note that considerations is different for a driver, where the ball sits on a peg a substantial distance from the ground. This section won't address that at all, just a ball on the ground or teed close to the ground.

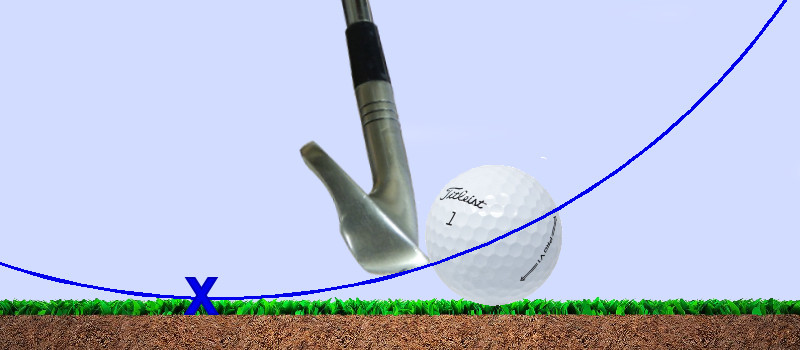

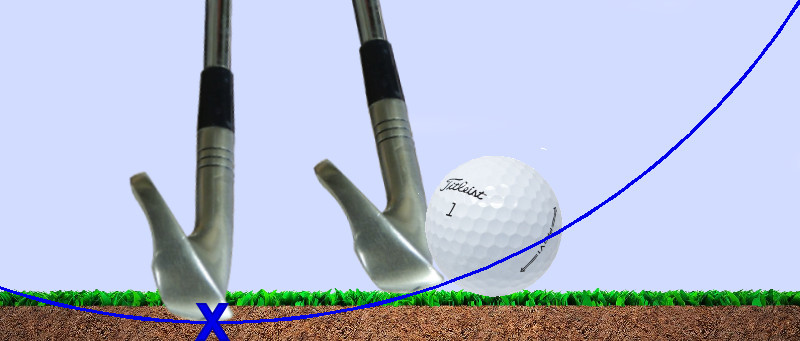

Ask a golfer to address the ball, then point with the club to where they think the lowest point of the swing should be. If they have never taken a lesson, they usually point at the ball. Their concept of proper impact, formed by intuition and reinforced by things like TV commentators saying, "He failed to get the clubface under the ball," looks something like this.

Before we proceed: Yes, there are a number of simplifications with this

image and discussion. None of them are oversimplifications

though, because we would come to the same qualitative conclusion if we were

rigorous about it. The simplifications merely make it easier to

understand and to analyze. Among those simplifications:

Why is the blue 'X'

above not the ideal way to strike the ball? It is mostly a matter of

tolerances; what happens if you miss that exact point? If you have

perfect control of the vertical and horizontal position of the swing

bottom, then you can get away with this and play good golf. Nobody has perfect control

with something as complex as a golf swing. Moreover, those athletes

with really good control are usually playing for stakes that say, "Your

missed shots better not be too bad!" So even they are worried about tolerances.- The curve is a more complex path than an arc of a circle, but an arc is a good approximation and we lose nothing of importance by treating it as an arc.

- I have exaggerated the curvature, so it is easier to make

the point with a smaller diagram.

- The arc will not continue as shown after impact with the ball. The momentum transfer of impact will necessarily drive the clubhead below the arc that is shown. But the ball is gone by then, so it will not affect what we say here about impact.

So let's look at what happens if you miss.

If the 'X' is too low, the shot will be fat.

If the 'X' is too high, the shot will be thin.

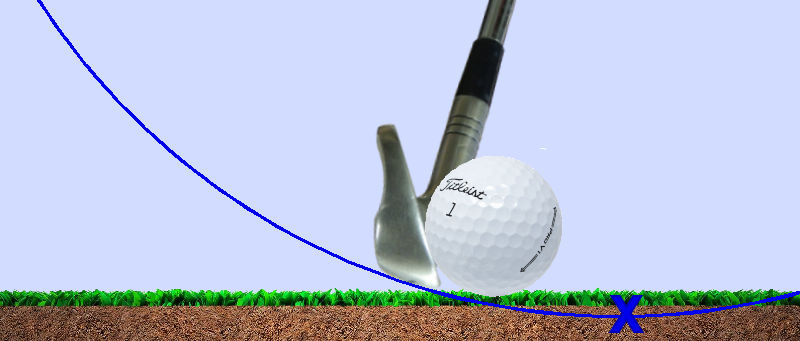

Suppose the 'X', the bottom of the swing arc, occurs before the clubhead reaches the ball. Let's assume it is the correct height to just skim the grass.

Usually, when a golfer does this, they conclude that they stood up or "came out of it" or "picked my head up" or some other form of "the clubhead was not low enough." It does not occur to them that the problem was a swing bottom that was too far back, just a swing bottom that was too high. So they correct the problem by trying to "stay down" better than they did last time. And here is what happens.

Here is the best placement of the swing bottom for both effective and reliable ball striking.

If your intent is a swing bottom about four inches after impact, you stand the best chance for solid contact between the clubface and the ball. This has been confirmed by both experience and analysis. You lose the least benefit of good impact for the usual tolerances of where a human swinging a golf club will put the blue 'X'. And this position of impact, with some forward shaft lean, gives additional advantages over other choices for the swing bottom, even if the swing bottom is executed perfectly. For instance:

- The shaft lean delofts the club, usually giving more distance without sacrificing spin.

- You can get more clubhead speed from this impact position

if you do it right. (We will see later how this allows you to apply

moment of force to keep accelerating the clubhead right to impact.)

- Bobby Clampett video on The Impact Zone. I've set the start to his "swing bottom" study, but the whole video is interesting.

- Bobby Clampett's line drill in the sand.

- Adam Young arguing that this is the single most important factor in hitting good shots.

- Adam Young on face contact and ground contact.

- Adam Young on golf shot compression, and why a downward angle of attack does not drive the ball into the ground.

Dysfunction

So

one job of biomechanics is to maximize function -- figure out how to

make the best possible shot. Distance -- or its most significant proxy,

clubhead speed -- is fairly easy to characterize as a biomechanics

problem. So a lot of biomechanics results are about generating clubhead

speed.Biomechanics has not been equally successful so far in another job: minimizing dysfunction. For instance, other things we might ask are:

- How do I swing a golf club so as to minimize my risk of injury?

- If I have a disability, how do I swing a golf club for the best possible shot that I can hit?

- If I have physical limitations that are not disabilities

(for instance, limited flexibility in the backswing), how do I swing a

golf club for the best possible shot that I can hit.

Last

modified -- Aug 27, 2024

|

|