|

|

Home ⇒ golf ⇒ biomech ⇒ Current Article |  |

Article

Contents

Physical principles for the golf swing

|

Function Consider

this lever.

It is strictly mechanical, except that one force on the

lever is produced by a muscle pulling at an attachment point on the

lever. Consider

this lever.

It is strictly mechanical, except that one force on the

lever is produced by a muscle pulling at an attachment point on the

lever.This kind of lever is the same as the wrench we looked at when we first introduced torque. The muscle force acts through a moment arm (lever arm) of Lm, and has the job of lifting or holding a weight at a moment arm of Lw. Since Lw is a lot larger than Lm, the muscle needs to pull with a much larger force than the kettlebell weighs. For instance, suppose the kettlebell weighs 25 pounds, Lm is one inch, and Lw is one foot (12 inches). That means the muscle's force of contraction must be 300 pounds (25*12/1) in order to just hold the lever horizontal, and more to raise the kettlebell upwards. In case you don't see a human joint right away, let's look at something that looks less like mechanical engineering and more like human anatomy. |

This

is mechanically identical, but made of flesh and bone instead

of metal. It is a human arm, flexed at the elbow.The green centerlines

cross at the hinge pivot of the elbow joint. We can think of the

distance from this pivot to where the biceps muscle attaches to the

forearm

bones as Lm, and the

distance from the pivot to the hand as Lw. This

is mechanically identical, but made of flesh and bone instead

of metal. It is a human arm, flexed at the elbow.The green centerlines

cross at the hinge pivot of the elbow joint. We can think of the

distance from this pivot to where the biceps muscle attaches to the

forearm

bones as Lm, and the

distance from the pivot to the hand as Lw.As noted, the biceps connects to the bones of the forearm at one end. The other end of the biceps connects to bone of the upper arm (the humerus) where it meets the shoulder. That keeps the pull exerted by the muscle parallel to the upper arm. I mentioned above that the muscle has to exert a much larger force than is exerted by the hand as a result of that force. A few implications:

|

But wait! We wanted to see how

we could push if muscles can only pull. The example we just

looked at,

flexing the elbow joint with the biceps muscle, is still much more of a pull

than a push. Let's try again. Here is another arrangement of forces around a joint. This time the forces are on opposite sides of the pivot, not the same side. So a pull with the muscle causes movement in the opposite direction, a push, at the "payload". As before, we accomplish this by having the muscle generate a torque at the pivot. The torque is the force exerted by the muscle times the moment arm Lm. And as before, the force at the payload is considerably attenuated because Lm is a lot less than Lw. We can look back at the classification of levers and see that this is a Class 2 lever, while the previous one, the one that lifted a kettlebell, is a Class 1 lever. |

Now let's once again relate this to

biological levers. Now let's once again relate this to

biological levers.This image shows how the the arm can be extended at the elbow, rather than flexed as in the previous example. The muscle that contracts is the triceps, and it lies opposite from the biceps against the humerus (the upper arm bone). The triceps connects to the bones of the lower arm on the outside of the elbow joint, instead of the inside the way the biceps does. In that way, it causes the elbow joint to straighten out, to push instead of pull. Let's add to our list of implications:

|

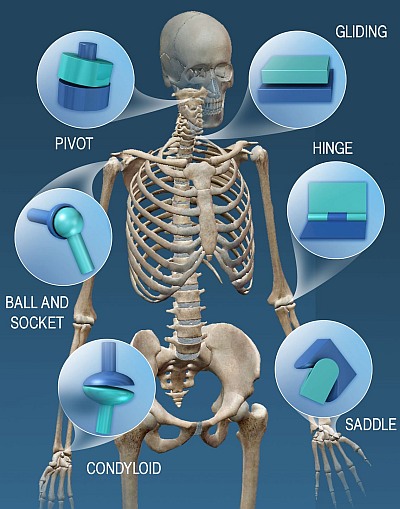

Types of jointsAny given joint has a certain amount of freedom -- degrees of freedom, or perhaps we could refer to them as dimensions or axes of rotation. We have been looking so far at an elbow, a simple joint with only one degree of freedom. You can extend your arm out straight or "curl" it at the elbow. So you need a one-axis hinge for the joint, and one muscle on each side of the joint to power it. (By "power it" I mean both execute contraction and control the motion.)Here is a diagram of many of the joints that figure into the golf swing. We can see the elbow represented as a hinge. The knee is also a hinge. Another important type of joint is the ball and socket, which allows three-dimensional motion, not just one like a hinge. We find it at the shoulders and hips. It allows the bones to sit at different angles to one another, and not just in one plane either like the hinge elbow. In addition, it allows the bone to rotate on its own axis. Of course, there must be a pair of muscles involved for each dimension. The angling can be achieved by two pairs of extensor-flexor muscles at right angles to each other. The axial rotation is achieved by a muscle wrapped around the bone in a shallow spiral. And of course we need a second muscle wrapped the other way to rotate the bone the other way. The condyloid joint (for instance, in the wrist) is a two-dimensional joint. It allows angles in two dimensions like the ball and socket, but no axial rotation. |

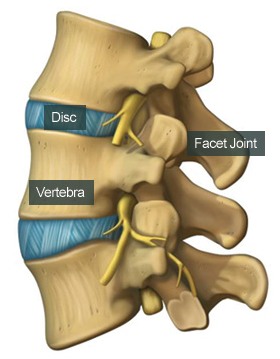

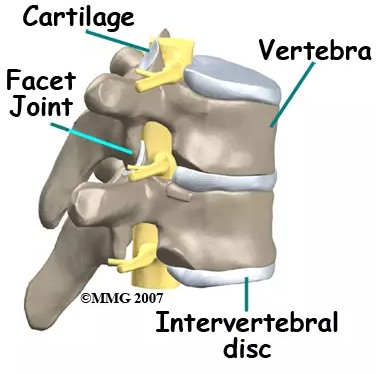

The

final type of joint I'd like to mention is in the spine. Our spine is

made up of a column of small bones called vertebrae, stacked one on top

of the other. between each pair of vertebrae is a strong but somewhat

flexible piece of cartilage called a disc. If a disc can compress a

little bit on one side or the other, then it allows the angle between

the vertebrae to change a bit. Even if it is only a couple of degrees,

it can be a total of over 60 degrees of total bend, given that there

are 33 vertebrae in the spine, and therefor 32 disc joints. So the

spine will appear to curve over its length, rather than "fold" at a

single pivot. In reality, the curve is the incremental folding of a lot

of short segments. The

final type of joint I'd like to mention is in the spine. Our spine is

made up of a column of small bones called vertebrae, stacked one on top

of the other. between each pair of vertebrae is a strong but somewhat

flexible piece of cartilage called a disc. If a disc can compress a

little bit on one side or the other, then it allows the angle between

the vertebrae to change a bit. Even if it is only a couple of degrees,

it can be a total of over 60 degrees of total bend, given that there

are 33 vertebrae in the spine, and therefor 32 disc joints. So the

spine will appear to curve over its length, rather than "fold" at a

single pivot. In reality, the curve is the incremental folding of a lot

of short segments.I described the spine as a column. It is often even called the "spinal column". But engineers know columns as deceptively fragile structures. If you compress a narrow column by pushing at its ends, you are not likely to see it fail in compression. Instead, as soon as some section of the column gets out of line a little bit, the whole column bends to one side; it fails not in compression but in bending.  To

illustrate, try this with a soda straw. Hold it vertically, with one

end on a hard surface, a surface rough enough that the end of the straw

will not slide around. Now press down on the tip with your finger or

hand. It will seem to be resisting your pressure very well... until it

suddenly "goes out of column" and fails. It starts to bend a little

bit, and that little bit cascades into a major failure so fast it seems

instantly. To

illustrate, try this with a soda straw. Hold it vertically, with one

end on a hard surface, a surface rough enough that the end of the straw

will not slide around. Now press down on the tip with your finger or

hand. It will seem to be resisting your pressure very well... until it

suddenly "goes out of column" and fails. It starts to bend a little

bit, and that little bit cascades into a major failure so fast it seems

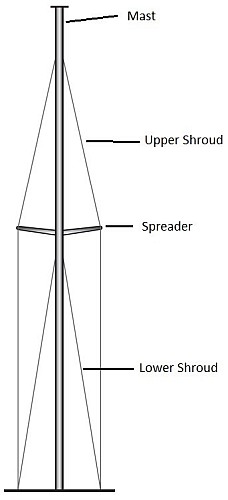

instantly.That nasty behavior of columns causes engineers to look for ways to reinforce them. Specifically, they reinforce them against sideways bending, or "buckling". Avoiding buckling was especially critical when much of the world's commerce depended on sailing ships. The mast of a sailboat is a tall, thin column, with a lot of compression, and also a lot of force being exerted by the sails to try to pull it "out of column". When that happens, a mast will snap. When you look at all the ropes on an old sailing ship, it is easy to be overwhelmed about their function. The function of a lot of that rigging was stabilization of the mast column. Let's look at a more modern sailing mast (left), which is a lot simpler. It has wire stays (called "shrouds" in this diagram), and rigid struts called "spreaders". The function of the stays and spreaders is to stabilize the shaft, to keep it in column. It does so by pushing sideways (the spreaders) and pulling sideways (the stays), reacting against any tendency of the mast column to buckle. There are vaguely similar structures in the spinal column, with very similar functions (though they look very different). There are protruding bones and facet joints which play the part of spreaders, and the muscles that span the protruding bones apply tension and act as stays. Yes, it's a lot more complicated than that. But unless you want to look closely at the biomechanics of spinal injuries, we don't need to understand the spine in much more detail than this. |

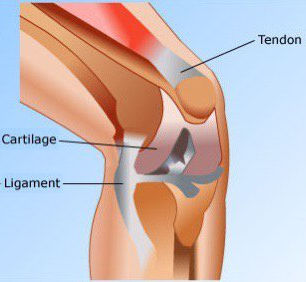

Tendons, ligaments, and cartilageWe know what tendons are; they connect muscle to bone. Their relation to joints is that they are the "transmission" that connects the "engine" (the muscle) to the "wheels", where the joints are "bearings". (Hey, I said up front we were going to treat the body as mechanical components to be used in engineering the golf swing. Hence the analogies.) Here's

a diagram that shows other components of the joints, ligaments and

cartilage. The joint itself is the knee. The function of each of the

components is: Here's

a diagram that shows other components of the joints, ligaments and

cartilage. The joint itself is the knee. The function of each of the

components is:

|

But there is a specialized cartilage function worth discussing in

the most complex moving structure in the body, the spine. In between

the 33 pieces of backbone, the vertebrae, there are structures called

discs. provide cushioning, adhesion, and lubrication of the joints

between the vertebrae. And cartilage is involved in each of those

functions. But there is a specialized cartilage function worth discussing in

the most complex moving structure in the body, the spine. In between

the 33 pieces of backbone, the vertebrae, there are structures called

discs. provide cushioning, adhesion, and lubrication of the joints

between the vertebrae. And cartilage is involved in each of those

functions.

|

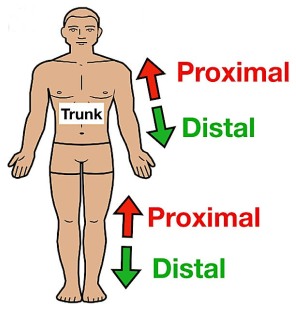

TerminologyIn order to understand articles and talks about golf biomechanics, you will probably need to understand a bunch of terms that biomechanists, physical therapists, patent lawyers, and other tech-talkers use. Sorry, but it is necessary, and a fair amount of it just has to be memorized. So let's dive in.The first terms we introduce are proximal and distal. I have to be honest; until I got into golf biomechanics (quite a few years into retirement) the only place I ever encountered those terms was reading patents. Patents are notoriously hard to read, and sprinkling them with terms like "distal" do not make it easier. But there is a real use for these two when discussing the structure of the body, or even the motion of a golf club. Proximal and distal make a distinction between nearer (in proximity) and more distant parts of a structure. For instance, when discussing the bones on the two sides of the elbow joint:

|

We already used the terms extension

and flexion

of a joint when talking about the elbow. A joint is put into extension

when the motion of the distal element extends

the length of the proximal element. (We could not have expressed that

without first defining proximal and distal.) Flexion, therefore, is the

motion opposite to extension. We already used the terms extension

and flexion

of a joint when talking about the elbow. A joint is put into extension

when the motion of the distal element extends

the length of the proximal element. (We could not have expressed that

without first defining proximal and distal.) Flexion, therefore, is the

motion opposite to extension.The diagram shows the directions for a couple of other joints, the knee and the ankle. They follow the definition, too. But it gets ambiguous when a joint has three dimensions of motion, and sometimes even with two. There can be movement in either of two planes that extends the length of the limb in question -- and sometimes there is not even a limb involved. So the names attached can be arbitrary, or at least seem arbitrary to someone trying to memorize the names. But we are going to mention two that we will be talking about in the golf swing:

|

Finally, we get to the wrist.

Things you need to know about the wrist: Finally, we get to the wrist.

Things you need to know about the wrist:

|

Last

modified -- Apr 3, 2023

|

|

|

"Proximal"

refers to the upper arm, the humerus, since it is on the side of the

elbow closer to the core of the body, the trunk.

"Proximal"

refers to the upper arm, the humerus, since it is on the side of the

elbow closer to the core of the body, the trunk.