What and Why

Let's start by looking at Lee Comeaux himself demonstrating the swing. Lee is a big guy and a powerful golfer, and this comes out in the swing. It's fun to watch the video.

While we're watching, let me express a recurrent concern. Lee is an excellent athlete with superb hand-eye coordination. He is big and strong. In evaluating the swing, I had to be constantly mindful of things that work for Lee because of this, and might not work for the average golfer. I have tried to make those distinctions, but I'm not certain how successful I was.

for

right-sided power:

for

right-sided power:- If you look at Homer Kelley's well-known but little-understood book, "The Golfing Machine" (printings from 1969 to 1983), he identifies the extension of the right arm as a source of power. (For instance, see chapter 6-B-1 of the book.)

- Consider the diagram at the right, a variant of what I often use to illustrate the classic double-pendulum model of the swing. As we all know (at least if we've seen the double pendulum model before), shoulder torque moves the hands in a circular arc, which provides the main power for the swing. But the torque has to be transmitted to the hands from the turning shoulders. Transmitting the torque is the work of the arms. The model assumes the arms to be a single rigid body. But in actuality, the hands can be driven along the circular arc by a pull from the left arm (blue arrow), a push from the right arm (purple arrow), or a combination of the two. Almost all instruction today focuses on the left arm pull, but there is no fundamental reason why any of the three choices could not be used. Just like the left-arm pull, the right-arm push has a component of its force that will move the hands along that circular arc. (Remember this diagram! We are going to use it in the analysis.)

- The dominant side of the body is stronger, so let's make it the dominant side of the swing. For a right-handed golfer, that means you want the right side and the right arm and hand to be dominant. Current instruction teaches a swing where left-arm pull is both the powering and the controlling factor in the swing. The major function of the right arm is to support the action of the left, and otherwise just not to get in the way,

- A push is stronger than a pull. Most strong moves in sports are more push than pull. So we should expect this to work for golf as well. But current instruction teaches a swing that is much more pull-oriented.

- More natural (comfortable) body positions means the body isn't resisting the swing. If you put the body (arm, leg, hand, etc.) in a position that human anatomy was not designed for, the body will make compensating moves to minimize the effect of that position. Lee's contention is that the modern golf swing is full of such contradictions, so it takes much effort to achieve any success training the body not to fight it. A swing that avoids such positions should be easier to teach, easier to learn, and more effective for more golfers.

- More natural body positions means less wear and tear, less injury, and greater golf longevity. This takes the previous point a step further. If the modern golf swing uses positions that human anatomy was not designed for, it may be dangerous to the golfers' health. There is little doubt that golfers suffer more than normal incidence of back problems, and maybe other similar injuries.

Keys To The Swing

Here I'll try to give a fair presentation of the fundamentals of the Lee Comeaux swing. I'm not Lee, so I may not present it exactly as he would. But I'm honestly trying to convey the essence as he explained it to me. Later, I'll go through this list again, with my own opinons of the keys. But for now, here's my understanding of the swing Lee is teaching:| Philosophy: | Whole

motion is (or at least should feel like) a hard right-hand punch

downward through the ball, thrown from the right shoulder

and reinforced

by a triceps-driven right-arm "piston". |

| Grip: | Ten-finger

grip, with the key fingers the last three of the right hand.

(Important note: For the conventional grip, it's the last three of the left

hand.) |

| Stance: | Lee

says "lean" rather than "bend". When asked for a distinction, Lee says

to think of an image:

"leaning" means you are "reaching" the club to the ball. Your weight

will

wind up on the balls of your feet instead of centered or back

on

the heels. Lee also recommends a stance with the left foot turned out a bit (most instructors recommend this), and the right foot drawn back a few inches. That is, fundamentally, a closed stance. But, unlike most closed stances, Lee keeps shoulders and hips aligned to the target line; only the foot line is closed. |

| Backswing: | Lift

club up with right hand, rather than one-piece takeaway. Shoulders

stay level, right shoulder maybe even lower than left. Club between the

hands. It's OK for the left arm to bend at the top of the backswing. |

| Weight shift: | Lee

proposes keeping the weight no farther back then the inside of the

right foot. But his is clearly a

stack'n'tilt move, keeping the weight pretty much left from address on. |

| Downswing: | Start

by extending right shoulder sharply down. Follow by pistoning the

right arm down and across the body. The effort should be extended well

past the

ball, as if you had "punched through" a boxing opponent. Your body will

do whatever weight shift and turn is needed to realize the feeling as

motion. This often turns out as an over-the-top move. Lee claims that over-the-top is the most powerful move a golfer can make. |

| Impact: | When

the hands reach the vicinity of impact, "Stand the shaft up". A few

other terms Lee has used for this move. "Stop the left hand and push

the right hand under it." "Slap the ball with the right hand." This

amounts to using hands, wrists, and arms to force a release of the club

at the ball. |

When I swung

right-arm-only, there was nothing but the right arm itself

to regulate the position of the clubface at the bottom of the swing,

and that right arm was also busy powering the swing. Right arm power

comes

from an extension during the downswing, so the timing of extension and

swing has to be really good to get the clubface on the ball. I kept

extending past the ground and hitting fat. Then I added the left arm.

With the fully extended left arm acting as a guide for the

hands,

there was no uncertainty where the clubhead was.

When I swung

right-arm-only, there was nothing but the right arm itself

to regulate the position of the clubface at the bottom of the swing,

and that right arm was also busy powering the swing. Right arm power

comes

from an extension during the downswing, so the timing of extension and

swing has to be really good to get the clubface on the ball. I kept

extending past the ground and hitting fat. Then I added the left arm.

With the fully extended left arm acting as a guide for the

hands,

there was no uncertainty where the clubhead was. A

week later, I spent another hour and a half on a Skype video call with

Dave Parker in Australia. Dave is putting together a

teaching guide for Leecommotion, and we wanted to compare notes on how

to present certain aspects of the swing. (Lee is knowledgeable and

passionate about the swing, but his descriptions can

be cryptic

without very clear video, and sometimes even with it. Proper

explanation of Leecommotion remains unsolved. Perhaps this article

will also help in that regard.)

A

week later, I spent another hour and a half on a Skype video call with

Dave Parker in Australia. Dave is putting together a

teaching guide for Leecommotion, and we wanted to compare notes on how

to present certain aspects of the swing. (Lee is knowledgeable and

passionate about the swing, but his descriptions can

be cryptic

without very clear video, and sometimes even with it. Proper

explanation of Leecommotion remains unsolved. Perhaps this article

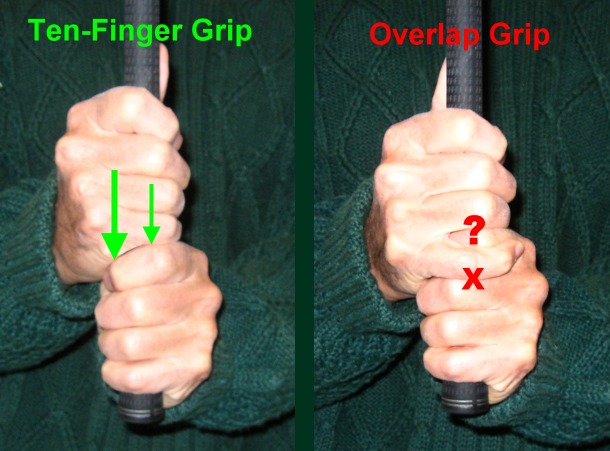

will also help in that regard.) The figure

at

the left compares the ten-finger grip with the overlap grip,

specifically with regard to transmitting force from the right hand (top

hand in the pictures) to the left. Note that what holds true for the

overlap is at least as true for the interlock grip.

The figure

at

the left compares the ten-finger grip with the overlap grip,

specifically with regard to transmitting force from the right hand (top

hand in the pictures) to the left. Note that what holds true for the

overlap is at least as true for the interlock grip. Lee

sent me this picture of a Hogan iron from many years ago, with Lee's

own

notes added to it. The clubhead featured an "under-slung" hosel that

added some steel behind the heel. The point was to move the center of

gravity (CG) closer to the shaft axis, to make it easier to close the

clubface.This idea may (or may not) have originated with Hogan, but it

has continued to pop up from time to time, especially in the designs of

Clay Long. He added weight to the hosel behind the heel in the Peerless

PHD. When Long moved to Cobra, he did the same thing

with their

Gravity Back irons.

Lee

sent me this picture of a Hogan iron from many years ago, with Lee's

own

notes added to it. The clubhead featured an "under-slung" hosel that

added some steel behind the heel. The point was to move the center of

gravity (CG) closer to the shaft axis, to make it easier to close the

clubface.This idea may (or may not) have originated with Hogan, but it

has continued to pop up from time to time, especially in the designs of

Clay Long. He added weight to the hosel behind the heel in the Peerless

PHD. When Long moved to Cobra, he did the same thing

with their

Gravity Back irons. But

what about early in the downswing? The left arm is extended, but

across the chest. The right arm is folded, not extended at all. Is the

double-pendulum a useful model there?

But

what about early in the downswing? The left arm is extended, but

across the chest. The right arm is folded, not extended at all. Is the

double-pendulum a useful model there?

The

second explanation has to do with bicycles.

I used to be very much into bicycling, and even got into the technical

aspects of it. (Big surprise, eh?) In the mid-1980s quite a few

cyclists who were also PC users designed their gearing ratios with a

program I developed. So a bicycle gear

analogy was a natural for me.

The

second explanation has to do with bicycles.

I used to be very much into bicycling, and even got into the technical

aspects of it. (Big surprise, eh?) In the mid-1980s quite a few

cyclists who were also PC users designed their gearing ratios with a

program I developed. So a bicycle gear

analogy was a natural for me.